Geology and Natural Heritage of the Long Valley Caldera

Human Impacts on Changing the Geological Landform and Ecological System in Eastern Sierra Nevada: Studies Based on the Field Survey of GEOL-G188 Class in 2015

Penfie Jiao

Abstract

Human factors are changing the geologic and ecologic environment. Based on the field survey sites of G188 class, this paper focuses on (1) the mining industry and air pollution in Death Valley, (2) the human-caused rockfall, fire, air pollution, and water availability decline in Yosemite, (3) the decreasing trend of Mono Lake water level and its relationship with LADWP. Climate change and its effects to the environment are all-pervasive and global. There are many future possibilities for the existence of humanity, extinction or "zero pollution" or sustainable survival. A macroscopic solution for present environmental issues is to recall the respect of nature.

Introduction

Around 100 years ago, John Muir, the greatest naturalist and "pilgrim" of the Sierra, described the human destruction of nature: "God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand tempests and floods. But he cannot save them from fools (Muir 22)." These words express his sympathy for the giant trees and his ardent love for nature. Muir devoted his whole life to protecting the Sierra and the Yosemite, and to reducing human damage to these treasures of nature. Human activities have impacted the geological and ecological environment of the Eastern Sierra Nevada throughout the history of civilization. However in recent years the impact of human activities has become more frequent and drastic than before. Today’s human population and modern technological development both require a large amount of resource consumption. Human influence is a more important factor than many natural processes in changing the geological system (Dutch 113). Considering the findings of the field survey of the G188 class from May 16th to 30th and the after-field research, the geological and ecological changes are quite evident. Based on the observations made in Death Valley National Park, Yosemite National Park, and Mono Lake (and its tributary river systems), this paper focuses on describing the significant, human-influenced environment changes and provides possible solutions for decreasing human damages to the Eastern Sierra Area.

The Formation of Places and Their Human Factors

Death Valley

Death Valley is a giant, low-elevation valley that sits in-between the Amargosa Range and the Panamint Range, and is located at the Southwest edge of the Basin and Range Province. As a part of the Basin and Range Province, the formation of Death Valley is continuous. The most ancient rocks formed around 1.7 billion years ago (National Park Service). Some geological evidence that formed 500 million years ago indicates the existence of a sea throughout the Death Valley area. Due to tectonic activities beneath the crust, land started to appear and the sea shifted westward as time passed. The Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada also formed by tectonics 250 million to 65 million years ago. For 65 million years to 2 million years, faults and joints weakened the crust, which allowed magma to erupt, flow, and reform the ground. The holes on the surface of the Earth that allow magma to go through are volcanoes. Their eruption recreated the geological and ecological system of Western North America (Oswald 35). The Artist’s Palette and borax deposits are products of this long-term, continuous eruption. However, these long-term volcanic activities also caused numerous species of animals and plants to become extinct during this period. About 3 million years ago, tectonic forces changed from compressional to extensional. These extensional tectonic forces formed more mountain ranges and valleys and Death Valley was formed during this era. Besides these constructive processes, destructive processes such as water erosion also played a huge role in forming the present landform. Alluvial fans down at the foothills are evidence of water erosion. Precipitation dissolved rock pieces into smaller pieces, and brought them down from the mountain peaks. After a long period of water accumulation, many mushroom-shaped patterns appeared down the foothills and leveled the low hills into a flat plain.

Human Factors of Death Valley

Human activities started to become more prevalent in the Death Valley area since the earliest prospecting occurred in the early 19th century. Today, more than a million visitors come to Death Valley National Park each year. Human factors, such as mining, air pollution, and global climate change are significant causes of local environment change.

Mining

The mineral resources of Death Valley were investigated during the California Gold Rush around 130 years ago. With the Mexican Cession of 1848, California and its surrounding regions were gained by the U.S. after the Mexican-American War. This sovereignty change provided opportunities for American entrepreneurs to invest in and acquire mineral resources. The Death Valley region contains a variety of metallic minerals including gold, antimony, copper, lead, zinc, silver, and tungsten ("Death Valley Historic Resource Study"). Borax, a mineral that dissolves in water and is used in detergents, is a comparatively more popular economic mineral (Lyons 24). The borax mining business made many people rich, such as William Coleman, the founder and producer of 20 Mule Team Borax (Lyons 25). Nonetheless, its price eventually decreased dramatically in the late 19th century, several years after the borax-boom. After two world wars and numerous government regulations, mining industries have become almost extinct in Death Valley – only five companies remained today. The mining industry destroyed the natural environment both directly and indirectly. Besides the acquisition of minerals, past occupation left plenty of rusty cars, battered appliances, and dilapidated tin shacks ("Death Valley Historic Resource Study"). These abandoned objects have slowly dissolved as time has passed, which has harmed the lives of local flora and fauna.

Figure 1. Dante’s View: The Best and Worst Days of 2001. Figure adopted from Death Valley National Park Service Website. [2001]

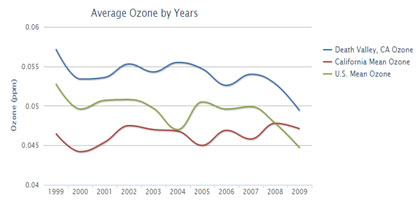

Air Pollution

Air pollution from nearby industrial facilities decreases the air quality in Death Valley, which increases the difficulty for sightseeing. Many visitors come to Death Valley for its seemingly endless scenery and vast variation in elevation. It is extremely hard to see valleys similar to Death Valley in other places of the world. However, the visibility of Death Valley is often not very optimal in spring and summer. The general trend in upper air shifts pollutants from western cities. In summer, southwest surface winds that carry pollutants from highly populated areas deteriorate air quality and visibility. Then, air conditions often recover in the winter, when the wind changes to the opposite direction (Hamilton 28). Pollutants often change form by the time they arrive and harm the local ecological system. Sulfates and nitrates increase the hazardous level of ozone, which increases the possibility of acid rain forming (Hamilton 29).

Figure 2. The decreasing trend of ozone in Death Valley. Figure adopted from usa.com. [2010]

Global Warming

The effects of global climate change on Death Valley are not exactly clear to researchers yet, but some phenomena are likely linked to global climate change. In fact, the burning hot valley has experienced cool summers in recent years. In August 2014, the average monthly temperature was about 20°F lower than the historical average for August (Weather Warehouse). The temperature was also comparatively low this year during the visit of the G188 class. The mild and comfortable weather of Death Valley was unexpected. Compared with the rainy, snowy, and chilly weather in the Sierra, Death Valley is probably more inhabitable. According to an observation of James Taylor, a natural scientist at Heartland Institute, the "remarkable cool weather" in Death Valley has become more frequent in the last 17 years. He thinks the abnormal temperature trend may not necessarily be the effect of global warming, but a combination of many other factors, which mostly remain unknown to us (Taylor 3).

Yosemite

Yosemite National Park, the third most popular national park in the U.S., is located west of the Mono Basin and East of San Francisco, which sits in the center of the Sierra Nevada. By relying on the advantage of valley-shaped landforms, snowmelt concentrates down at the bottom of the valley and enriches the water resource. Tuolumne and Merced are two main river systems in the Park; they travel all the way to the other side of California Valley and provide water supply to thousands of local residents (Peterson 53). Yosemite is well-known for its beautiful, natural sceneries. John Muir described the Park as "by far the grandest of all the special temples of Nature he was ever permitted to enter." Muir was objective about natural beauty; more than 4 million visitors follow his words and come to enjoy the enchanting sights each year. The gigantic granite domes are unique features of Yosemite, which are hard to find in other places in the world. These igneous, granite rocks are evidence of great, historical volcanic eruptions. Their smoothly polished surfaces make for convenient, geological rock study and also give evidence for the prior existence of glaciers.

Human Factors of Yosemite

In contrast to Death Valley, where human activities are popular in the business world because of its rich mineral concentration, most of the human footsteps in Yosemite are residents and visitors. Concerns over environmental problems caused by people often arise from the massive number of visitors. The purpose of the National Parks is to serve the general public, but a surplus amount of visitors can increase the possibility of hazards and destroy many natural terrains. Fire, rockfall, automobile pollution and the decline in water availability are all the major effects of human activities in Yosemite.

Figure 3. A fire near the entrance of Hodgdon Meadow Campground on September 23, 2013. Figure adopted from National Park Service Website. [2013]

Fire

"Fire and smoke are as much a part of the Yosemite ecosystem as water and ice (National Park Service)." Most of the fire sources are naturally generated, such as by lightning strikes. In summer, thousands of lightning strikes occur within the park, and some of them have the possibility of triggering a large fire. The natural fire, such as the fire caused by lightning, is a type of wildland fire. Wildland fire accounts for about 80% of all the fires in Yosemite (Fimrite 14). It is a natural process that provides opportunities to change. While fire destroys the original vegetation coverage, it also accelerates the dissolving process of plants and provides energy resources for new lives. Other disturbance forces, like floods and earthquakes, also work similarly as fire; they re-construct the old landform by destroying old vegetation and allowing new vegetation to grow.

Human-caused fires account for about 20% of all fires in Yosemite. These fires do not belong to the category of natural fire, are unnecessary, and should be suppressed. However, not all fires are in the suppression zone for firefighters. Firstly, topographic difficulty gives resistance to the extinguishment of these fires. Many places in Yosemite are unreachable for humans. Secondly, the Yosemite fire brigade does not have the number of firefighters nor the technology to cover the whole park and thus only 17% of the park is under full-time fire protection (National Park Service). Therefore, unwanted fires are not always suppressible. A decrease in human-caused fire is strongly encouraged in order to protect the natural scenery of Yosemite.

Figure 4. A rockfall that occurred on Highway 140 at approximately 11:00 a.m. December 30, 2010. Figure adopted from Yobanet.com. [2010]

Rockfall

Rockfall is recognized as an important natural force in Yosemite. Rock falls from the mountain due to rocks splitting, time, earthquakes, and most importantly, gravity. Many rockfalls were unrecorded and unknown to people before many visitors came to Yosemite during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The general public and the Yosemite National Park Service changed their perception of rockfall immediately following the November 16th, 1980 rockfall at Yosemite Falls Trail, which caused three fatalities and at least nineteen injuries (Stock et al. 9).

Similarly to fire, most rockfalls are caused by natural processes (Stock et al. 5). Frequent human activities could accelerate the flexibility of rocks, which increases the possibility of rockfall. Yet the human factor is not quite as powerful as natural forces and many potential future rockfalls are likely to occur in places that are tough for humans to step on. Rockfalls directly caused by human activities are practically impossible. Therefore, decreasing the number of visitors does not necessarily prevent rockfall hazards. The primary goal for Yosemite National Park Service, as it describes in its report, is to "prevent visitor injuries and fatalities within the limits of available resources (Stock et al. 11)." Many other studies also point out the effects of rockfall on human activities and the necessity to improve protective facilities, but no studies focus on humans’ effect on aiding in the occurrence of rockfall (Govorushko 44). There remains a possibility that a lack of study may account for the difficulty of measuring and recording this human effect. The park does not have the resources and technology to precisely record and trace human movements. Humans’ roles in accelerating rockfalls take an almost immeasurable amount of time and have a nearly undeterminable amount of influence, thus it is not a simple task to determine the exact details of human related rockfalls.

Figure 5. A crowded parking lot in Yosemite in the mid-1960s. Figure adopted from Argonaut Book Shop. Photo by Rondal Partridge. [1966]

Automobile Pollution

Private automobiles were admitted to enter the park in 1913 (Chiriboga 1). Today, they have become the most popular transportation tool in the park. The grand size of Yosemite, 1190 square miles, makes people incapable of walking through all the scenic spots. Allowing travel by car is necessary for the convenience of the visitors, but it can also cause air pollution that threatens human health and park wildlife. Automobiles are the main producer of ozone pollution in the park. Ozone is not a direct pollutant, but its secondary chemical precursors, nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons, are harmful for the local ecology and the residents of Yosemite (National Park Service). Many forms of wildlife are in danger because of this air pollution. For example, human pollution has caused a dramatic population decline in several frog species, including the endangered mountain yellow-legged frogs. If the trend of human pollution continues, all mountain yellow-legged frogs will be extinct within several years (Chiriboga 26).

Decline in Water Availability

Yosemite has abundant water resources. High elevation mountains provide low-temperature storage for snow, and valley-shaped landforms assist the melting snow in forming rivers and lakes. Water is a significant factor in shaping the landform of Yosemite and maintaining the vitality of local flora and fauna. The Tuolumne and Merced rivers are two main water systems in the park; all the creeks and streams eventually join one of them (Wuerthner 80).

In recent years, the water availability has had a trend of decline. James Lutz, an environmental scientist and professor at the University of Washington, has declared that there is a present water deficit in Yosemite and a possible future decline to come. He and his colleagues calculated the water balance in Yosemite National Park using "a modified Thornthwaite-type method" (Lutz, van Wagtendonk, and Franklin 936). One finding of their field research was that the water deficit for all species raised by 5% in 300 years. They predict that the future deficit may increase to 23% in 30 years. A main cause of the present deficit and the possible continuing deficit is climate change or global warming (Lutz, van Wagtendonk, and Franklin 946). A continuously, slowly rising temperature would provide less opportunities for snow to concentrate on the mountain peaks of Yosemite, which would decrease the amount of snow melt in the long term. The influence of climate change may seem minor and ignorable at the present time because the increase in temperature is counterbalanced by an increase in precipitation. However, this period will eventually pass and be replaced by a constant or declining precipitation in conjunction with a rising temperature. This future will require more evaporative demand and will decrease the amount of snow stored among the peaks of Yosemite. If this prediction becomes true in the future, the water resource and ecological system of Yosemite will be confronted with their biggest crises.

Figure 6. These tufa towers were once under the lake. Figure adopted from IU G188 Class Website. Photo by Michael Hamburger. [2015]

Mono Lake

Mono Lake is located east of Yosemite National Park and the Sierra Nevada. It has a lake area of 50,000 acres and an average depth of 56 feet. The lake level has been fluctuating around 6,400 feet in the recent century ("Quick Facts"). The formation of Mono Lake is related to the local historical volcanic activities. In 1908, oil prospectors discovered an ash layer from the Long Valley eruption at Paoha Island and the age of Mono Lake was inadvertently discovered. Since there is more lake sediment under the ash layer, Mono Lake might have been formed before the Long Valley eruption 760,000 years ago ("Volcanic History Evidence of Recent Eruptions"). The Long Valley eruption had a tremendous influence in forming the geological landforms of the Western U.S. It was 2,500 times larger than the Mt. St. Helens blast of 1980, and blasted 150 cubic miles of ash. Many sites that the G188 class visited this summer are direct or indirect products of Long Valley eruption, such as the Obsidian Dome, Glass Creek Dome, Owens Valley, Mammoth Mountain, etc.

Human Factors of Mono Lake

Los Angeles Aqueduct

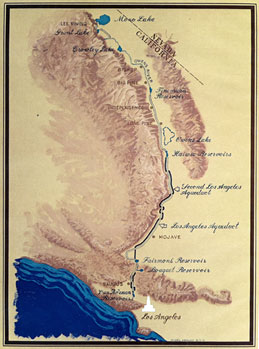

The arid environment of Los Angeles requires a large amount of water from outside of L.A. The Los Angeles Aqueduct system was designed to deliver fresh water to the city from the Eastern Sierra, including Owens River, Crowley Lake, and Grant Lake, etc. Mono Lake and its tributary rivers are the furthest water station of this system ("Los Angeles Aqueduct Facts"). As a result of the Great Basin effect, water that flows into Mono Lake does not flow out. A million years of mineral salt concentrations made the lake extremely salty. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, LADWP, designed an aqueduct near the tributary rivers of Mono Lake to avoid the saltiness. The first aqueduct was completed in 1913, and the second aqueduct in 1970. These two segments of aqueducts stretch for a total of 419 miles and have a flowing capacity of 20 cubic meters per second.

The water level of Mono Lake declined rapidly after the LADWP diverted its tributary streams in 1941. It declined 25 feet in 20 years ("The Mono Lake Story"). Many tufa towers that were previously covered in water are being forced to emerge out of the lake. A decrease in the volume of water has also caused an increase in salinity, which has harmed the lives of 4 trillion brine shrimp. Brine shrimp make up the base of the food chain in Mono Basin and are also the major food source for birds ("The Brine Shrimp Life Cycle"). The local ecological system would be seriously damaged if brine shrimp died because of the continuously decreasing lake level. In 1994, under the work of many organizations and individuals, the State of California passed Mono Lake Decision 1631. Decision 1631 admits the necessity for Mono Lake to maintain a moderate water level and gives monitoring rights to the Mono Lake Committee.

Figure 7. Map of the Los Angeles Aqueduct – its route and facilities, in eastern and southern California. Mono Lake is the blue circle on the top. Figure painted by Migel Abalos. [1971

Conclusion

Similarly to natural processes, many human factors are changing the geological and ecological environment in the Eastern Sierra Nevada region. In Death Valley, the mining industry excavates plenty of underground minerals. Air pollution from nearby cities is also slowly affecting the ecosystem in this area. In Yosemite, human-caused rockfall, fire, and air pollution, has increased the danger for the deterioration of the health of local residents and the environment. The growing population of Los Angeles requires more water supplies, which directly causes a decreasing trend in the Mono Lake water level. Besides those human factors, climate change is the most significant human factor. It is an accumulation of booming human population and centuries of industrialization (Weart 29). Steven Dutch, a geology professor at the University of Wisconsin, asserts the severity of human activities in nature in his essay "The Earth Has a Future" (Dutch 113). Dutch says that "human impacts already equal or surpass many natural processes (Dutch 114)." Human impacts are influential, many natural forces are less powerful in comparison with modern human technology and global warming is one typical example.

History is not an unbroken line; it does not always march toward an inevitable end point. The geologic features are formed in processes that were "highly dynamic and changeable (Dutch 113)." The location of earthquakes, the size of volcanic eruptions, and the speed of lava flows are highly randomized and unpredictable. No one could accurately predict all of them and their future variations. However, that does not mean all geological changes are unpredictable and imperceptible. Some future geologic activities may take place in our generation, such as the scenario in the movie "Super Volcano." There are many possibilities for the outcomes of these future environmental issues. Steven Dutch argues for the possibility of "zero pollution." In the future, humans may have the technology to "derive energy and mineral resources from space rather than from Earth’s surface (Dutch 114)." Global warming and its effects would slowly disappear after a huge reduction. It is also possible that our future generations can remain within the limits of environmental sustainability (Dutch 122). New technologies are invented as substitutes for resources while the human population remains within a moderate boundary.

As the carbon dioxide record annually increases and slowly affects the global ecosystem, a possible macroscopic solution for environmental issues in present-day world, I think, is to respect and cherish Nature with a conscience and love.

Works Cited

1994 SWRCB Mono Lake Decision 1631 (text). Mono Lake Clearinghouse, n.d. Web. 16 June 2015.

Chiriboga, E. People, Cars Causes Problems for Yosemite. Our National Parks. N.p., 09 Dec. 2009. Web. 14 June 2015.

Death Valley NP: Historic Resource Study (History of Mining). National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, 01 Mar. 1981. Web. 16 June 2015.

Dutch, S.I. The Earth Has a Future. Geosphere 2.3 (2006): 113–124. Web.

Fimrite, P., and Sernoffsky, E. Yosemite Fire near Half Dome Forces Airlifting of 85 People. SFGate. N.p., 09 Sept. 2014. Web. 14 June 2015.

Govorushko, S.M. Natural Processes and Human Impacts: Interactions between Humanity and the Environment. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012. Print.

Los Angeles Aqueduct Facts. Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, n.d. Web. 14 June 2015.

Hamilton, J. Death Valley National Park. Edina, MN: ABDO Pub., 2009. Print.

Lutz, J.A., van Wagtendonk, J.W., and Franklin, J.F. Climatic Water Deficit, Tree Species Ranges, and Climate Change in Yosemite National Park. Journal of Biogeography 37.5 (2010): 936–950. Web.

Lyons, C. Borax Has Meant Big Business in California’s Death Valley. Western Enterprise Feb. (2011): 1–3. Print.

National Park Service. National Park Service. U.S. Department of Interior, n.d. Web. 13 June 2015.

Muir, J. Our Forests and National Parks, by John Muir, 1901. http://college.cengage.com/. N.p., 1901. Web. 15 June 2015.

Oswald, M.J. Your Guide to Death Valley National Park. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

Peterson, D., et al. Air Temperature and Snowmelt Discharge Characteristics, Merced River at Happy Isles, Yosemite National Park, Central Sierra Nevada. Workshop, 2004 C3 – Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Pacific Climate (2004): 53–64. Print.

Quick Facts about Mono Lake. Mono Lake Committee, n.d. Web. 14 June 2015.

Stock, Greg M., et al. Quantitative Rock-Fall Hazard and Risk Assessment for Yosemite Valley, Yosemite National Park, California. USGS - Yosemite National Park - PhD 30332 (2012): n. pag. Print.

Taylor, J. Global Warming? Death Valley Shatters Cool Temperature Record. Heartland Institute, 05 Aug. 2014. Web. 14 June 2015.

The Brine Shrimp Life Cycle. Genetic Science Learning Center. University of Utah, n.d. Web. 14 June 2015.

Volcanic History: Evidence of Recent Eruptions. Mono Lake Committee, n.d. Web. 14 June 2015.

Weart, S.R. The Discovery of Global Warming. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2003. Print.

Wuerthner, G. Yosemite: A Visitor’s Companion. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 1994. Print.

[Return to Research Projects] [Return to Sierra Home]