Geology and Natural Heritage of the Long Valley Caldera

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and its Effects on Mono Lake

Liz Kemker

Abstract

The effects that diverting water away from the Mono Basin were devastating and included a reduction in the bird population and the lake level decreasing. This seemed to be just a repeat of Owens Valley. After witnessing this, several groups fought against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power for the salty lake. These groups were able to beat the LADWP with the Public Trust Doctrine. Several aqueducts were used to divert the water and the construction of these proved to be very difficult. I personally believe that what the LADWP did was wrong in an environmental view but they did take the correct legal steps. The steps that they did take were legal. The steps were weak and were overturned quickly.

Introduction

The history of Mono lake has been a very controversial one that has been entangled with environmental concerns as well as legal aspects. Water and Power has been seen as a ‘bad guy’ since 1941 when they began taking water from the Mono Basin. Even movies have used the name of Water and Power as the villains, for example Tank Girl. To the Department of Water and Power, the Mono Basin was a precious jewel that they could use for its water for the population of Los Angeles or to generate electricity. Even though the water from Mono lake is not consumable due to its high saline levels, the lake itself is abundant with life. When the level of the lake started to decrease many environmentalist began to fight against Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. This was the beginning of a fight that would last for several decades for the future of Mono lake and its fragile ecosystem. The modern success of the state has as a result been funded upon a massive reorganization of natural environment through public water development.

www.pashnit.com/roads/cal/Hwy120east.htm

A photo of Mono lake’s surreal beauty, directly adopted from website

The absurd, yet beautiful landscape can be attested to the vast difference of geological surroundings. Before 1941 Mono lake was 6,417 feet above sea level and was just one of the vast number of lakes in the Great Basin of the North. There are five major streams that feed the Mono lake, as well as a small number of smaller streams, but there is no place that water from the lake flows out. As stated earlier, the water from the lake has a 10 percent mineral content causing the high salt concentrations according to The United States Department of Agriculture. The salty water itself from the lake is not useful to humans but the five streams of fresh water were highly desired by LADWP. There are two streams that are capable of transferring 142,000 acre-feet of water per year to Owens River’s headwaters. These creeks are Rush and Lee Vining. There is a smaller creek, Mill Creek, that was never considered due to its small flow and the finical costs were too high to develop it. Snowmelt is another way that water reaches Mono lake. Snowmelt begins in April and goes all the way through June, the maximum runoff is in the months of May and June. The snowmelt either flows into the five streams and enters the lake or flows into smaller tributaries to the lake. Because snow is only a seasonal occurrence, approximately 40 percent of the total flow per year occurs in the late spring through early summer. Other then there being no streams that flow out of Mono lake there are other means for the water to escape the lake such as evaporation and water escaping through the soil. According to the LADWP in 1987 they estimated the annual evaporation rate to be 42 inches per year, which makes evaporation approximately 50 percent of the total lake water loss. The basin that Mono lake is located in has become filled with layers of lake lacustrine, colluvial, alluvial as well as glacial sediments. These sediments range from unconsolidated to poorly consolidated which allowed the flow of groundwater through the layers.

www.oikonos.org/projects/predators.htm

A map that shows some of the main streams that feed Mono lake, directly adopted from website

It was once said that Mono lake is a dead lake, much like the Dead Sea, and that in this lake there resided no life, just the salty water. While there may not be a substantially large amount of life living directly in the water, the few specimens that do make Mono lake able to sustain a vast array of other life forms. There are no fish in this lake, due to its high alkalinity, but there is a vast abundance of brine shrimp. Alkali flies live in this supposedly dead lake along with the shrimp. These two habitants of Mono lake feed thousands of migrating birds every year. Vast amounts of Wilson’s Phalaropes, Eared Grebes and Red-necked Phalaropes use Mono as a key stopping point in their migration paths. This is a stop to and from Central and South America every year. Nomadic birds are not the only birds that enjoy Mono, California Gulls use the lake for a nesting ground. The number of gulls is so large that the only other place in the world that has a great concentration is the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The California Gulls nest on the two islands in the lake, Negit and Paoha. This was a grave problem when the water level dropped dramatically due to LADWP diverting water away from the lake. When the water level dropped land forms leading from the shore to the islands, bridges began to appear. These land bridges allowed for predators walk to the islands and eat the eggs and/or the young birds. The population of California Gulls was drastically reduced in 1977. Because of the large bird population, as well as the gull massacre of 1977, the National Audubon Society took an interest in the conservation of the waters of Mono lake. The reduction of water did not only affect the gulls at Mono. When the level of water dropped, the saline level increased and even though this did not directly affect the birds it did kill the brine shrimp. Brine shrimp are a prime source of food for all of the birds that go to Mono lake and a loss of a food source obviously affects the population of the organism that is consuming them. Diverting water had disrupted the delicate teeter totter that was life in the Mono lake.

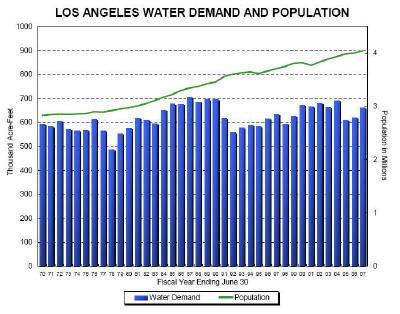

www.monobasinresearch.org/

The relationship between the population of Los Angeles and the water need, directly adopted from website

mceer.buffalo.edu/.../06/20-02/03_LADWP.asp

The district of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, directly adopted from websiteThe members of LADWP did not want a repeat of Owens Valley. Owens Valley was very much like Mono lake before Los Angeles Department of Water and Power started to take water from the valley. LADWP, however, did take the legal formalities in order to attain the water rights of Owens Valley. According to the State of California, “To prevent a repetition of the Owens Valley conflict, the committee recommended adoption of legislation similar to the states in New York requiring that a municipality which seeks to extend its water system to a distant source of supply much first submit its plans to a state commission which would also receive and adjudicate all claims for damages arising from that development.”

The LADWP constructed a 223 mile long aqueduct that was completed in 1913 in order to bring water from the Owens Valley to the city of Los Angeles. Because the water of the Owens River now flows to Los Angeles, Owen Lake no longer exists. The water rights of this area were bought through deception and this outraged the people of Owens Valley. The people of Owens Valley were so livid that in 1924 there were areas of the water system that farmers attacked. Even after the violence the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power did not stop the construction of the second aqueduct. This second aqueduct was completed in 1970 and because of this more water was being taken out of the valley. Because of this extra water being taken out the springs and seeps dried up and disappeared completely. Due to the effects of what happened in Owen Valley people were very against the same thing happening in the Mono Lake basin, one man in contradiction of water being taken from the Mono lake basin. “They raped the Owens Valley and bled Inyo County dry. Mountains make safe neighbors…Our water is for agriculture. Los Angeles shall not drill one well…Let LADWP go where sea water abounds. Stick it up in El Segundo!” thundered the Bakersfield Californian in an editorial from August 1, 1976.

http://geochange.er.usgs.gov/sw/impacts/geology/owens/

A map of Owens Valley with Dust trap and town locations, directly adopted from website

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power viewed the waters pouring into Mono lake as a precious jewel that could simply be picked up and taken away. There were several factors pertaining to why water from Mono lake seemed to be perfect. The climate in the Mono Basin area is very arid and therefore difficult for many plants to grow, let alone thrive. The weather is not the single reason for little to no agriculture, the terrain around Mono lake basin is very rugged . This would make it nearly impossible for tractors and other agricultural vehicles to plow and tend to crops. A State Engineer had commented as early as 1925 that, even if the Colorado River water was immediately available, “It would be good business to secure the supply from Owens Valley and Mono lake Basin because of its superior quality and delivery by gravity.” Water that is delivered by gravity is very cost efficient, virtually free. William Mulholland had protected a benefit of a greater worth: the assurance that there would be no farther development within the Mono Basin which might conflict with the Los Angels’ final construction of the aqueduct addition.

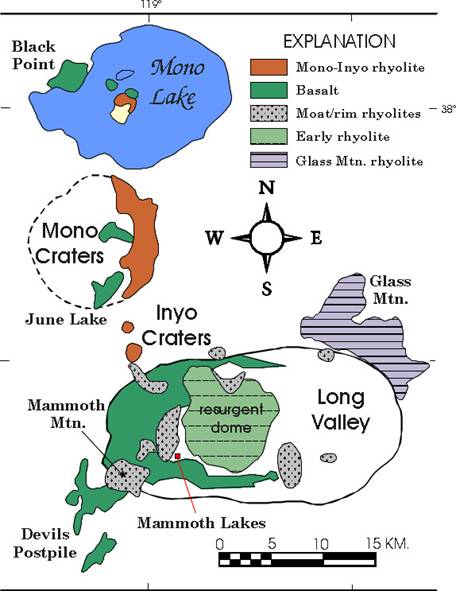

pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2185/appenda.html

Mono lake and the eruptive styles and years when it happened, directly adopted from website

Throughout the history of the construction of the aqueducts in the Mono lake Basin there have been several difficulties. These problems have not only been encountered by the LADWP or the people living in these regions, but the construction workers as well. The tunnel thatneeded to be completed was 11.3 miles long and needed to be drilled through the craters of an extinct volcano. This was the first time that a task such as this had ever been attempted. In 934 the progress of the on the construction of the tunnel was hindered by steam, hot water and volcanic gases that were encountered according to the City of Los Angeles, Department of Public works. The Mono lake region encompasses three individual, but possibly related volcanic complexes. These eruptions began around 200,000 years before present. There are two island in the Mono lake, Negit and Paoha, are in fact two of the thirty only just active vents. The Mono Basin has a remarkable geological makeup that the engineers of LADWP did think would cause a problem to them as the they diverted water.

In the year of 1941 the city of Los Angeles was finally done with the construction of the Mono Craters Tunnel. At the completion of the tunnel the city began to divert the precious water away from Mono lake to Los Angeles. A letter was written to the Los Angeles Board of Public Commissioners stated that the mono supervisors were complaining of that the withdraw of their land was retarding the county’s growth. The supervisors demanded to know the city’s true intentions. Los Angeles was very protective of Mono lake and took the defensive. The city did not respond to the supervisors and the question was help in abeyance for half of a year. However, in the year 1945 the Charles Brown Act was ratified. This grant required that Los Angeles permit the existing tenants of the land of Inyo County the first right to refuse lease renewals and the sales of its lands. The city of Los Angeles was finally starting to understand that they had deeply upset many people of Mono lake as well as others who loved the lake. There were several different groups who began to fight for the lake and its water. The first group to take action against the LADWP was the National Audubon Society. They were, however, not the only group.

www.csc.noaa.gov

A visual aid for the Public Trust Doctrine, Image adopted from website

http://www.audubon.org/

The logo for the National Audubon Society, directly adopted from websiteThe National Audubon Society started the beginning of several decades of legal battles over between various environmental groups and LADWP. In 1979 this group brought a Public Trust Suit against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. The Public Trust Doctrine originated from Roman law concepts of communal property. According to Institutes of Justinian 2.1.1., under Roman law, the air, the rivers, the seas and the seashore were incapable of private property ownership; they were dedicated to the use of the public. The purpose of the Public Trust Doctrine is the affirmation of the duty of the state to protect the people’s common heritage of tide and submerged lands for their common use as ruled in the case National Audubon Society v. Superior Court in 1983. The idea of what common use is has changed throughout the years. The original idea of what common use was related to water was water-related commerce, navigation and fishing. None of these activities are common in Mono lake. Trade nor navigation were common on the lake because of the high winds that would easily capsize a boat. Fishing in Mono lake was, and still isn’t, an option due to there being no fish in the lake. However, more has been added to what common use is. The California Supreme Court has said that now the Public Trust Doctrine includes the right of the public to use the navigable waters of the states for bathing, swimming, boating and general recreation purposes. One of the main recreation purposes was bird watching and this is the reason that the National Audubon Society got involved. The mission of the National Audubon Society is to conserve and restore natural ecosystems, focusing on birds and other wildlife

for the benefit of humanity.

http://www.ladwp.com/library/img/logo_main3.gif

The logo to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, directly adopted from website

It is possible that lands that are protected by the Public Trust Doctrine can be used for industrial purposes, there are three guidelines that must be achieved in compliance with the doctrine when leasing tidelands for assembly of permanent structures to achieve a lessee’s development plan: (1) the structure must absolutely promote uses sanctioned by the statuary trust grant and trust law generally, (2) the structure is required to be supplementary to the support of such uses, or (3) the structure must oblige or augment the public’s satisfaction of the trust lands. The objective of the public trust is always evolving so that a trustee is not burdened with outmoded classifications favoring the original and traditional triad of commerce, navigation and fisheries over those uses encompassing changing public needs as ruled in National Audubon Society v. Superior Court, supra.The National Audobon Society had called the LADWP out on a set of guidelines that was several centuries old that they were in violation of. The California Supreme Court ruled that the Public Trust Doctrine did in fact apply to LADWP’s alterations from streams that fed Mono lake. The National Audubon Society was not the only group that took legal actions against what the LADWP was doing. In 1991 Native Americans, two state agencies (the State Lands Commission and the Department of Fish and Game), two environmental groups (the Sierra Club and the Owens Valley Committee) and others solicited the Appellate Court to permit them the status of amici curiae or friends of the court. These groups wanted this in order to establish the legality of the 1991 EIR. The EIR stands for Environmental Impact Reports and the EIR addresses the impact the LADWP had on the environment due to its massive supply that was being taken by the second aqueduct. The environmental impacts were the rapid decrease of the water line which led to the death of a hefty number of birds. As well as the water that was needed by the people of Mono Basin was being removed.

geology.csupomona.edu/docs/stop23-2.htmA map of Mono Basin and Long Valley with eruptive remnants

The war for the waters that fed Mono lake started in 1941 when water first started

to be diverted away from the lake. Between the start of the war and the end of it there were many legal processes, court appearances and protests on part of the lake as well as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. The city of Los Angeles was not happy with the amount of water that it was receiving from the Mono Basin. LADWP began to pump even more groundwater then it had disclosed before beginning the construction of the second aqueduct. Mono Basin was one of these sources to feed the city. This decision was made in 1972 and five months after the completion of the second aqueduct. At the same time, the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”) was endorsed. The Court of Appeal decided that Los Angeles’ water rights license should be modified to require a bypass of water adequate to maintain fisheries that had been in existence prior to Los Angeles’ stream alteration.The war over the water of the Mono Basin was a very long and trying one. In my personal opinion the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power should not have taken the water from the streams that feed Mono lake. The repercussions that were a result of the water being removed was a travesty to the environment as well as to the people who lived there. The LADWP did take several legal steps in order to attain the water rights of the Mono Basin, however the state of California turned down these rights. I would like to believe that a company as powerful as the LADWP would be able to attain the correct legal actions in order to keep their water rights. The future lawyer side of me agrees that the LADWP did follow the correct legal actions, but it is a shame that they did not do enough research to have a solid legal battle. If I were one of those lawyers who fought for LADWP or was a sponsor I would be very upset that after taking the correct legal steps that I would be turned down of my rights. There is another side of me that would like to believe that the people of LADWP would realize that after the Owens Valley disaster and violence they would give diverting water from Mono more thought. I believe that people should think of how their actions will effect their surroundings. If I had to be a part of this battle I would have fought for Mono lake. Especially after visiting Mono lake and seeing first hand the alien like beauty of the area, it absolutely boggles my mind that someone could destroy such a remarkable place.

In conclusion, what the LADWP had done to the Mono Basin region may never be completely healed. The years of legal battles have left bad blood between the people of Los Angeles and those who loved and fought for their beloved lake. The battles that were taken part of by the LADWP were, in technical terms, the correct steps to take. They did not, however, think of a very large road block that was brought up by the National Audubon Society. This was the Public Trust Doctrine. The building of the aqueducts to take the water away proved hazardous to build due to past geological phenomenon. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power may have believed that what they were doing would not have caused legal ramifications or upset the people, they were horribly wrong. The LADWP caused significant damage to Mono lake but it was the beautiful Mono Basin that paid the price.

Work Cited

1. Finney to Los Angeles Board of Public Service Commissioners, January 26, 1924, ibid.2. Institutes of Justinian 2.1.1

3. Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. June 8, 2009 <www.ladwp.com>.

4. National Audubon Society v. Superior Court (1983) 33 Cal. 3d 419. 441

5. State of California, Legislature, “Senate Report of the Special Investigating Committee on Water Situation in Inyo and Mono counties,” Journal Senate (May7, 1931)

6. State of California, Office of the State Engineer, Letter of Transmittal and Report of the State Engineer Concerning the Owens Valley-Los Angeles Controversy to Governor Friend William Richardson, by W. F. McClure (1925), p. 11

7. States Geological Survey". USGS. June 8, 2009 <www.usgs.gov>.

8. William L. Water and Power. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1983.