Geology and Natural Heritage of the Long Valley Caldera

In Search of A Healthy Balance At Mono Lake

Elaine Harris

Introduction

California's Mono Lake in the Twentieth Century tells a story of massive mid-Century water diversion by the City of Los Angeles, followed by environmental collapse, giving rise to late-Century citizen activism, lawsuits, public hearings, court decisions, and finally an attempt—still ongoing--to find and maintain a new balance between human and environmental needs.

Mono Lake is the story of how the 19 th Century American ethos of “taming the wilderness” created a disaster when humans attempted to take too much out of Nature—in this case, it was water. Nature reacted to the loss of fresh water at Mono Lake with dying birds and fish, dirty air, and other dramatic environmental results. Students—college teachers and students, fishermen, and other naturalists—reacted by organizing and filing lawsuits. Then the courts and governmental agencies finally reacted in the 1980s and 1990s by declaring new “rights” for nature, and setting limits on human exploitation of natural resources.

Geology and Natural history of Mono Lake

Mono Lake is a large saltwater lake, located near the California/Nevada border, about 160 miles east of San Francisco and 250 miles north of Los Angeles . The lake sits in the Long Valley Caldera, and was formed after a volcanic eruption approximately 750,000 years ago. In the middle of the lake there is a recent volcanic cone, called Negit Island .

The lake is fed by five creeks that flow east into the Great Basin from the Sierra Nevada Mountains along the eastern edge of Yosemite National Park . The streams are Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, Walker and Mill, which have a combined average annual flow of approximately 187,000 acre feet of water. As of 2005, the lake has a surface area of about 45,133 square acres and a volume of about 2.6 million acre-feet. It is a “dead” lake, with no outlet. Ongoing volcanic activity at Mono Lake is evidenced by lake sediments found on Pahoa exposing bishop tuff. The unique chemistry of the lake is shown by the lake's “tufa” formations—rock towers formed underwater when water seeping from calcium springs on the floor of the lake mixes and reacts with the salty lake water to create limestone. Since 1941, the level of the lake has fallen over 40 feet as a result of water diversions by the City of Los Angeles; this has exposed the tufa formations, which now stick up from areas of the lakeshore.

Tufa formations at Mono Lake

Mono Lake 's nutrients feed algae, which in turn support the lake's thriving populations of Artemia monica (a species of brine shrimp) and alkali fly. These rare animals are great bird food, which support the more than 118 bird species that stop at Mono Lake during the summer time.

Two mating brine shrimp

Human impacts on Mono Lake since the mid-1800'sMono Lake 's first known human inhabitants were the Native Americans known as the Kutzadika'a (“fly eaters”) People. A staple of the Kutzadika'a diet was the alkali fly pupae, which is high in fat and protein. The Kutzadika'a lived only part of the year in Mono Basin ; in the Fall they would travel to pinion pine forests in the Great Basin , where they collected pine nuts.

The first large groups of Europaen settlers in the Mono Basin were miners, who arrived beginning in 1860, to mine gold and silver in the nearby Bodie Hills. Beginning in the 1870s, the miners built the town of Bodie , which in 1878 held a population of over 5,000. To build the mine shafts, the miners logged Jeffrey Pine from the surrounding mountains; they also cut the forests to fuel the stamp mills and to heat the miners' houses. To transport the timber across the Mono Basin , a railroad was build from the town of Bodie to top of Bodie hills. A staple of the early miners' diet was seagull eggs from Mono Lake 's seagull rookeries, resulting in the decimation of the lake's seagull population. Bodie was inhabited through the 1930s, when it was no longer economical to mine the Bodie Hills. Today, Bodie is a well-preserved ghost town.

During the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries, cattle ranches developed in the Mono Basin . By 1940, 9,200 cattle, 825 horses, and 25,000 sheep were grazed in the Mono Basin . Ranchers tapped Mono Lake 's source creeks for irrigation ditches, and the grazing cattle destroyed the creek beds. The height of local irrigation diversion was reached in the late 1920s, when an annual average of 60,000 acre-feet of water was diverted from Lee Vining, Walker, Parker, and Rush Creeks between 1925-1929.

By 1916, a hydroelectric dam was operating on Rush Creek . Other dams on Rush Creek created Gem Lake and Agnew Lake .

History of the City of Los Angeles ' water diversions from Mono Basin

Under the leadership of chief water engineer William Mulholland, the City of Los Angeles in the first decade of the Twentieth Century developed a source of water in the Owens Valley , situated only 15 miles south of the Mono Basin . Construction of the 240-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1913, resulting in diversion of the Owens River 225 miles south to Los Angeles .

Los Angeles Aqueduct with Owens Valley in the background

Beginning in the 1930's, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power turned its attention to water development in the Mono Basin, specifically to Rush, Lee Vining, Walker, and Parker creeks. Los Angeles' applications to divert water from these creeks were approved in 1940 by the California Department of Public Works Division of Water Resources, the predecessor state agency to the State Water Resources Control Board. Although the board recognized that water diversions would harm the Mono Basin , the diversion was approved, based upon provisions of California water law (now Water Code Section 1254) which state that domestic use is the highest use of water.

In 1941, pursuant to its permits, Los Angeles completed construction of a dam and reservoir on Rush Creek . The resultant lake, Grant Lake , was the source of an 11-mile pipeline through the mountains to the headwaters of the Owens River in the neighboring Owens Valley . And so the Mono Basin 's streams were diverted by Los Angeles into the Owens Valley Project. This water collected in Lake Crowley where it is diverted into three hydroelectric plants.

In 1974, Los Angeles received licenses 10190 and 10192, which allowed the Department of Water and Power to build a second “barrel” of the Los Angeles Aqueduct between Haiwee Reservoir and Los Angeles . This allowed for an average of 82% of runoff from Rush Creek and lee Vining creek. The average yearly diversion in 1974-1989 of all four of Mono Lake 's source creeks was 83,000 acre-feet per year.

Mono Lake Environmental Problems Due to Los Angeles Water Diversion

By 1982, eight years after completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct's second “barrel,” the waters of Mono Lake reached their lowest historic level, 6,372 above sea level. This was 45 feet lower than the lake's historic 1941 high level of 6,417 feet above sea level. The 45-foot drop in lake level resulted in a 30 percent shrinkage of the lake's surface area. Between 1941 and 1982, Mono Lake almost doubled in salinity, raising from 51.3 g/l (grams / liter) in 1941to 99.4g/l in 1982.

Mono Lake is second only to the Great Salt Lake as the largest breeding grounds for the California Gull. Eighty-five percent of seagulls that breed in California breed at Mono Lake . Gulls typically nest on islands and rocky areas. When the level of Mono Lake dropped to 6,379 feet above sea level in 1979, it exposed a “land bridge” of dry land between the historic lakeshore and Negit Island , the home of the lake's largest colony of breeding seagulls. Coyotes followed the land bridge to Negit Island , resulting in the destruction of 33,000 gulls and gull eggs. At the lake level of 6,372 feet in 1982 coyotes ate 30% of the gull population from Twain Island and Java islets.

Researchers say in the early 20 th century Mono Lake was visited annually by hundreds of thousands of migrating waterfowl. Today there are only 11,000-15,000 flying into Mono Lake every year. This decline is directly related to the decrease in fresh water inflow, because the ducks and other waterfowl sit on the fresh water. According to bird researchers, Mono Lake would have to be restored to a surface elevation of 6,405 ft for total restoration of the waterfowl population.

In 1982, the shrinking lake exposed 18,500 acres of alkaline lakeshore, compared to the 1941 lakeshore. The exposed area was susceptible to wind storms blowing salt and alkaline deposits. High Eastern Sierra winds created dust storms of microscopic dust particles, called “PM-10,” which causes asthma, attacks, breathing difficulties, and eye and nose irritations in humans.

The dewatering of the creek beds of Parker, Lee Vining, Rush, and Walker creeks, destroyed the creek ecoyststem which produced a loss of recreation and fishing. Floods in the late 1960's and early 1980's cut deep into the creek beds, stranding former meadows and wetland habitat. By 1989 a total of 204.4 acres of mature riparian woodlands and over 100 acres of meadow had been lost on the four diverted creeks. The water shortages created a lack of biological diversity. There was also a lacking of nutrients in the creek waters which reduced the nutrients in Mono Lake.

April 9 th 2002 . Dust storm on the north shore of Mono Lake

History of the Save Mono Lake Movement

After completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct's “second barrel” in 1974, over 80 percent of the source-creek water flow was diverted from the Mono Lake Basin , and the lake level was dropping each year at an alarming rate. David Gaines, a Stanford teaching assistant and avid birder, came to Mono Lake in 1974 to study the environmental effects of water diversions. Assisted in his study by undergraduates from University of California campuses at Davis and Santa Cruz , Gaines authored “An Ecological Study of Mono Lake, California,” published by the U.C. Davis Press in 1977. In 1978, Gaines founded the Mono Lake Committee.

David Gaines the birder and co-founder of the Mono Lake Committee.

In 1979, The Audubon Society, joined by the Mono Lake Committee, Friends of the Earth, and four Mono basin homeowners, filed the first lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles , National Audubon Society v. Superior Court. The plaintiffs argued that the amount of Los Angeles' water exports was excessive, resulting in damage to “public trust” assets, including water and air quality, scenic and recreation values, and fish and wildlife. The case in 1983 reached the California Supreme Court, which agreed with the Plaintiffs that Los Angeles had violated the “public trust.” The Supreme Court ordered that the City's water diversion permits be reexamined, to strike a reasonable balance between the City's domestic water needs, and the “public trust” doctrine.

Other groups that joined the legal fight were Cal Trout, a non-profit conservation group focused on protecting streams for fish and recreation. In 1985 Cal Trout brought suit to amend the licenses the State Water Resource Control Board to include the Fish and Game code. They fought for the licenses to restricted Los Angeles ' water diversion and make them release enough water to allow fisheries in the streams running into Mono Lake.

The California Water Quality Control Board's Decision 1631 (1994)

Eleven years after the California Supreme Court's decision in the Audubon Society case, the California Water Quality Control Board—the successor to the state agency which issued Los Angeles' original permits—concluded extensive hearings on the Mono Basin water diversions. Based upon extensive scientific testimony and public hearings, the Board in 1994 issued its Decision 1631, which established 6,391 feet above sea level as a target for a healthy Mono Lake. The Board found that the 6,391-foot lake level would protect nesting birds, reduce air pollution from the dust storms, restore fisheries in the source creeks, and protect the quality of Mono Lake 's water from becoming too salty.

Decision 1631 held that Los Angeles would not be able to divert any water from the creeks at lake levels below 6,377 feet. Between lake levels of 6,377 and 6.380 feet, water diversions of 4,500 acre-feet per year would be allowed; and at lake levels between 6,380 and 6,391ft, Los Angeles would be allowed to divert 16,000 acre-feet from Mono Lake 's source creeks. At lake levels above 6,391 feet, no limits beyond fishery-protection would be placed on Los Angeles ' water diversions. The Water Board set a target date of 2014—20 years—to reach the 3,391-foot level. If Mono Lake has not reached that level by then, the State Water Board will reconsider and further hearings will be held.

Mono Lake since Decision 1631

Since 1994, the LADWP has been required by Decision 1631 to monitor the creeks and conditions of the lake. Today the monitoring includes the lake level, the surrounding creek vegetation, vegetation mapping, and fish and waterfowl surveys. The information is available on the Department's website.

The goal of the LADWP and Mono Lake Committee is to allow the creeks to restore themselves by allowing more water into them. It is agreed that human intervention in some areas will help the ecosystem build itself faster. In 1999, DWP filled Rush Creek with old tree trunks and other wood debris to increase the complexity of the creeks. In the fall of 2004 the LADWP put a new dam into Lee Vining creek, which allows sediments to flow freely. The dams off of each creek release more water in the spring and summer months during the summer runoff season. This mimics the spring flows which are the times fish are spawning. Side channels have been opened off of Rush Creek , in order for more ground water over a larger area to rehabilitate the surrounding vegetation.

Lee Vining Creek. June 3, 2005

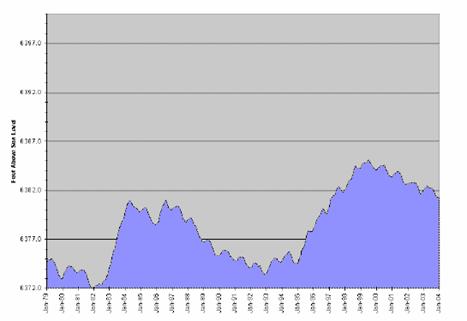

In the 10-plus years between Decision 1631 and June, 2005, Mono Lake has risen to a high-water mark of 6385.1 feet above sea level in July, 1999, but since then has receded after several dry winters to 6381.8 feet above sea level as of June, 2005. (See the graph below, and the real-time date on the LADWP's and Mono Lake Committee's websites, cited at footnotes 18 and 23.) As the lake grows in surface area, there is more opportunity for water to evaporate. Before the lake reaches 6,392 ft. above sea level, the dust storms will continue to violate air quality standards for the Mono Basin. In the years 2000-2002 there were fourteen recorded air quality violations.

The Gull population has continued to change. In 1994 the gull population was 60,000 to 65,000 adults. In 2000 there were 39,830 gulls and in 2003 there were a recorded 49,300 gulls that were nesting in Mono Lake. In the late 1990's there were about half as many chicks in each nest as in 2003. The low level of chicks being born is affecting the recent numbers of Gulls at Mono. It takes four years for a chick gull to be an adult and have chicks. Meromixis—a water condition where the nutrient-rich lower lake waters remain do not mix with the warmer fresh water near the lake's surface--believed by researches to have contributed to the low chick birth in the late 1990s.

Mono Lake water levels in January from 1970-2004

The Mono Lake Committee is still very active in protecting Mono Lake and educating the public about the history of Mono Lake. There are many educational tours given to children from Los Angeles. The Committee publishes the quarterly Mono Lake Newsletter, and maintains a highly informative website. It is present at annual meetings with the LADWP that address concerns of the rehabilitation process and the water levels of Mono Lake. The Committee has inspired other environmental movements, including Living Lakes, an organization dedicated to restoring lake habitats, and the Owens Valley Committee, a citizen watchdog committee for the Owens Valley.

Conclusion: Changing Values Give Hope for Survival

In “Cadillac Desert,” his history of water development in the American West, author Mark Reisner cites changing American values as the basis for environmental preservation efforts in the late Twentieth Century. “What it all boils down to is undoing the wrongs caused by earlier generations doing what they thought was right…. By the [1970s], however, America's values were utterly different….After damming the canyons and dewatering the rivers in order to spill wealth on the land, we are going to take some of the water back, and put it where, one could argue—as more and more Westerners now do—it really belongs. Law has been the ignition, but a great, almost epochal shift in values has worked as the engine of change.”

At Mono Lake , since Decision 1631 in 1994, the lake level, bird counts, and air quality still vary up and down from year-to-year due to natural forces. But the underlying societal values have changed from the old standard of domestic use as the “highest and best” use, to public recognition that water use is subject to a “public trust” that balances domestic use with the needs for water and air quality, recreation, scenery, wildlife and land formations.

Bibliography

1. Mono Basin Research, http://www.monobasinresearch.org.

2. Mono Committee Website, http://www.monolake.org.

3. Reisner, Marc. “ Cadillac Desert : The American west and its Disappearing Water.” Penguin books, New York . 1986.

4. Reis, Greg. “ Lake Level Watch.” Mono Lake Newsletter Winter 1997. http://www.monolake.org/newsletter/97winter/wchwin97.htm

5. Reis, Greg. “Lakewatch” Mono Lake Newsletter Winter 2000.

http://www.monolake.org/newsletter/00winter/3.htm6. Hite, Justin. “ California Gull Research Continues On: Reasearch Still Extremely Relevant to Mono Lake 's Recovering Health” Mono Lake Newsletter Spring 2004.

7. Young, Gordon. “The Troubled Waters of Mono Lake .” National Geographic, October 1981. p. 504-519.

8. Roecher, Craig. “State of the Lake Report Inspires Audiences: Third Annual Presentation focuses on Birds of Mono Basin.” Mono Lake Newsletter Fall 2002.

9. State of California State Water Resources Control Board: Decision 1631. November 1994. http://www.appliedhydrogeology.com/Mono%20Lake%20-%20Water%20Resources%20Control%20Board%20Decision%201631.htm